Over the next 12 months we’ll be taking a deeper look at the past decade since Katrina on the Gulf Coast and into the future with a regular blog series, K+10.

New Orleans was devastated by floodwaters from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 due to multiple failures of an incomplete and inadequately designed levee system. This was compounded by decades of manmade wetlands loss that reduced the city’s natural storm-surge barriers.

Moving forward, improvements are being made along multiple lines of defense in order to effectively manage the risk from large storms. An extensive look at our critically-important wetlands can be found in our two-part Restoring Our Wetlands coverage.

We’ll now take a look at the various components of New Orleans’ flood protection system, why they failed, and the post-Katrina improvements made thus far.

Levees

Levees are made of dense clay and usually covered in grass. Due to their incredible mass, it is rare for a levee to fail if it has a proper foundation, is made of solid clay and is not overtopped.

One of the primary failure points for levees came where they met floodwalls or other cement structures. These areas often led to increased levee erosion. To combat this, many levees like the one meeting a floodwall above have been “armored” at such points with rocks and/or cement covering them instead of grass.

Floodwalls

Floodwalls are made with deep footings of pilings and are steel-reinforced concrete. One of the primary causes of floodwall failure was “scouring” that occurred during overtopping. Water spilling over the top of the floodwall eroded the bare ground behind the floodwall until its foundation gave way. This has been mitigated by installing “splash pads” of concrete next to the floodwall, such as has been done in the Lower Ninth Ward, above.

Floodwalls have been further strengthened with deeper footings and in some cases, multiple sets of footings set at angles. Both tactics help prevent floodwalls from tipping or being pushed over by the force of water being held back. Conditions of the soil beneath floodwalls must be carefully examined to ensure they are securely planted, as sandy or boggy soil will allow water to flow through and can wash floodwalls out from below.

Pumping Stations

With the city surrounded by levees and floodwalls, there is nowhere for rainwater to go, so it must be pumped out. Huge water pumps invented by A. Baldwin Wood solved this problem at the turn of the 20th century, and led to significant expansion of the city beyond the high ground along the natural river ridges. New Orleans’ rainwater now flows to the lowest parts of the city, where huge pumping stations using Wood’s pumps were built. Some have pipes large enough to drive a car through. The pumping stations pump the water up into outfall canals, from which they drain into Lake Pontchartrain.

Outfall Canals

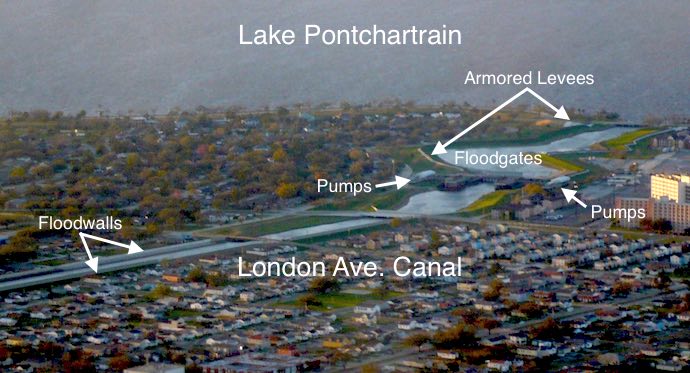

New Orleans’ three outfall canals (17th Street, Orleans Avenue and London Avenue [above]) were built at a higher elevation than the surrounding area so that they’d drain by gravity to Lake Pontchartrain.

Because the canals were left open to the lake, Katrina’s storm surge was able to backflow into them. A long period of stalemate between local and federal flood protection authorities over how best to protect the canals from storm surge resulted in the installation of “I-wall” floodwalls around the canals. At the time of Katrina, sections of these floodwalls failed at water levels well below their rated capacities.

Repairs and improvements have been made to the outfall canal floodwalls and improvements to reduce dependency on them are on the way (below).

Outfall Canal Floodgates and Pumping Stations

Temporary outfall canal closure structures are already in place for the three canals, with the London Avenue Canal closure pictured above. Permanent structures are currently under construction. In order to continue draining rainwater when the outfall canal floodgates are closed, additional sets of pumps have been installed at the mouth of each canal, to pump rainwater past the closures and into Lake Pontchartrain.

Industrial Canal and MRGO

In addition to protection along Lake Pontchartrain, the three outfall canals and at the edges of the metro area, New Orleans has miles of levees and floodwalls throughout its center, providing protection from navigable canals built for shipping and commercial purposes. These include the Industrial Canal (above), Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) and the Harvey Canal.

The MRGO was particularly devastating during Katrina, funneling storm surge from the open ocean at its mouth 76 miles away directly to the Industrial Canal in the heart of the city (above; downtown NOLA can be seen in the distance on the left and Camp Restore is just out of view to the right). The MRGO has since been permanently blocked near its mouth, and further protection has been added in the form of the IHNC Lake Borgne Surge Barrier.

IHNC Lake Borgne Surge Barrier

The granddaddy of all floodwalls in the New Orleans area (and the world, for that matter), the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier is simply enormous, made of 1,271 concrete pilings, each 66 inches wide and 144 feet long. Jutting 25 feet above water level, the top of the floodwall is wide enough to drive a truck on. Several floodgates allow ships to pass through under normal conditions.

Seabrook Floodgate

The Industrial Canal was also open to storm surge from Lake Pontchartrain in 2005; the Seabrook Floodgate Structure was completed in 2012 and was successfully operated during Hurricane Isaac to close off the Industrial Canal from the lake.

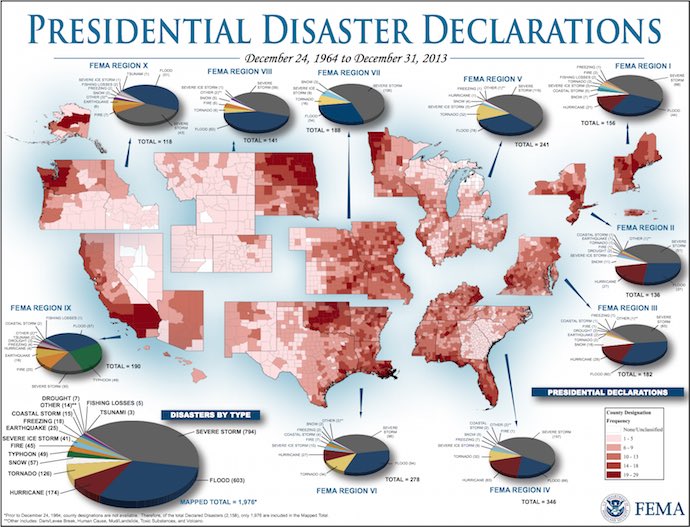

National Impact

As the above chart from FEMA illustrates, every region of the United States has experienced significant numbers of flood-related disasters in the past 50 years. Over half of all the counties and parishes in the United States are protected by levees. Check out the interactive map at levees.org to see if your county is one of them.

This floodwall is located atop a levee in Columbus, Ohio. The proper design, construction and maintenance of levees is of critical importance not only in New Orleans, but across most of the United States, including many areas that have dry to even desert conditions.

The levee failures following Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent redesign and rebuilding of the system around New Orleanss are key opportunities for engineers, officials and the public to learn from past mistakes and implement improved systems across the country.

What You Can Do

Significant progress has been made in improving New Orleans’ levee system, and yet it is important to remember it’s only one part of a multiple-lines-of-defense strategy. There is still significant work required for wetlands restoration, some of which is being accomplished by volunteers. We must remain vigilant on both a local and national level to learn from the mistakes of the past and prevent them from being repeated.